Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics

B. Maasoumy, K. Port, B. Calle Serrano, A. A. Markova, L. Sollik, M. P. Manns, M. Cornberg, H. Wedemeyer

Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(11-12):1365-1372.

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Background Drug–drug interactions (DDIs) in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection became a potential challenge with the introduction of direct-acting anti-virals (DAAs). Both currently approved DAAs, the protease inhibitors (PIs) telaprevir (TVR) and boceprevir (BOC), are substrates and inhibitors of P-glycoprotein and the cytochrome P450 3A4, which are regularly involved in DDIs.

Aim To analyse the risk for DDIs in patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection considered for PI treatment at a tertiary referral centre.

Methods The first 115 consecutive patients selected for a PI therapy at Hannover Medical School were included. All changes to co-medication before and during PI treatment were documented. Drugs were checked for DDIs with TVR and BOC using DDI websites and the respective prescribing information.

Results Out-patient medication contained 116 different drugs. Median number of drugs/patient was 2 (range 0–11). The risk for DDIs was substantial for 38% of the drugs affecting 49% of patients. Only 4% of the drugs were strictly contraindicated. DDIs between a PI and drugs newly prescribed during anti-viral therapy were considerable in 42% of the patients. Suspected DDIs were managed by dose adjustments and discontinuation of co-medication in 7% and 21% of the patients respectively.

Conclusions Many patients with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection are affected by potential DDIs if treated with a protease inhibitor, but only in a minority of cases co-medication is strictly incompatible. Overall, the challenge of DDIs is time-consuming, but well manageable by a careful review of the patient's drug chart and monitoring during treatment.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection majorly contributes to the increasing prevalence of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide.[1, 2] Anti-viral treatment may lead to clearance of the virus, defined as a sustained virological response (SVR). Achieving SVR lowers the risk for hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma and reduces overall mortality.[3-5] The development of direct-acting anti-viral agents (DAAs) has significantly improved HCV therapy, as DAAs increase SVR rates and may soon even lead to interferon-free treatment options.[6] In 2011, the first generation of this new drug class was approved for the treatment of HCV genotype 1 infection: the protease inhibitors (PI) telaprevir (TVR) and boceprevir (BOC). Since then, the new standard of care for the treatment of chronic HCV genotype 1 infection became triple therapy consisting of pegylated-interferon alpha (Peg-IFN), ribavirin (RBV) and either telaprevir (TVR) or boceprevir (BOC) in many countries. Both PIs markedly improved the probability of SVR compared with previous dual therapy.[7] Under optimal conditions, up to 88% achieve SVR after 28–48 weeks of triple therapy.[8-10] However, new PI-containing triple therapies are also accompanied by new problems like a more complicated dosing regimen[8, 9] and a higher number of severe adverse events, in particular, in those with advanced liver disease.[11-13] Furthermore, with the introduction of DAAs, hepatologists are now facing drug–drug interactions (DDIs) as an additional challenge of HCV therapy. Both approved PIs are strong inhibitors of the cytochrome P450 CYP3A4. Furthermore, TVR and, to a lesser extent, BOC are metabolised by CYP3A4. In addition, both agents are also inhibitors and substrates of the membrane transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which affects TVR more than BOC.[14, 15] As a result, there is a potential risk for DDIs with other drugs metabolised by the same pathways. An increase in drug concentrations may cause toxicity and lead to adverse events. On the other hand, a decrease in drug concentrations may lead to a loss of therapeutic efficacy and, if the PIs are affected, this may lead to treatment failure due to emergence of viral resistance and subsequently a virological breakthrough. Recently, there have been a couple of valuable review articles that indicated drugs that, in principle, should not be administered or only with caution due to anticipated DDIs.[14, 15] However, despite the relative attention DDIs have gained in the discussion of PI therapies, there are rather limited data on the extent that HCV patients are really at risk for DDIs due to their regular out-patient medication. Overall, it remains unclear to what extent DDIs reach clinical significance when HCV patients are considered for DAA treatment. We aimed to investigate the clinical significance of DDIs in a real-life cohort of patients with chronic HCV infection selected for PI treatment in a tertiary referral centre.

Patients and Methods

Patients

The first 115 consecutive patients who were selected to receive treatment with a PI, either TVR or BOC, at the hepatitis out-patient clinic of Hannover Medical School were selected for this study.

Assessment of Drugs Taken before and During PI Treatment

All 115 patients were routinely asked for their regular out-patient medication prior to the start of PI treatment, which importantly also included any kind of self-medication. For the assessment of the out-patient medication at baseline, we documented all drugs that were taken regularly, except for drugs started during Peg-IFN/RBV lead-in phase, which were considered drugs started during anti-viral treatment. In cases of combination products, e.g. ramipril/hydrochlorthiazide, each individual substance was counted separately. In contrast, mixtures of minerals or vitamins as well as herbal medication were counted as only one drug if they contained four or more ingredients. Of the 115 patients, 14 had to discontinue during or directly after the Peg-IFN/RBV lead-in phase due to a virological failure or treatment intolerance. As a result, only 101 patients were exposed to a PI. These 101 patients were followed during PI treatment and all drugs newly taken during or due to anti-viral therapy were assessed.

Estimation of the Risk for Drug-Drug-interactions

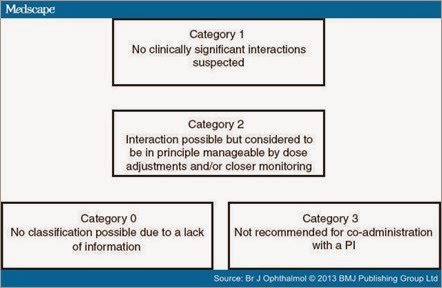

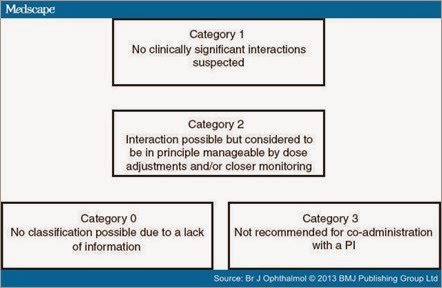

All drugs taken before or during PI therapy were carefully analysed for potential interactions with TVR and BOC using the web resource http://www.hep-druginteractions.org, the package label of TVR, BOC and the analysed drug, known interactions with other strong CYP 3A4 inhibitors (using ritonavir and the web resource http://www.hiv-druginteractions.org) as well as additional sources if more information was needed to draw a reliable conclusion. Drugs were categorised into four groups according to the suspected significance of interactions with the PIs: 'No clinically significant interactions expected' (Category 1), 'Interaction possible but in principle manageable by dose adjustments and/or closer monitoring' (Category 2), 'Not recommended for co-administration with a PI' (Category 3) or 'No classification possible due to a lack of information' (Category 0) (Figure 1). In doubt, or in cases of discrepancies between the two HCV PIs, the more sever risk category was chosen.

Figure 1. The four different risk categories of drug–drug interactions with an HCV protease inhibitor: Category 1 (low-risk): 'No clinically significant interactions expected'; Category 2 (significant, but not severe risk): 'Interaction possible but in principle manageable by dose adjustments and/or closer monitoring'; Category 3 (severe risk): 'Not recommended for co-administration with a PI'; Category 0 (uncertain risk): 'No classification possible due to a lack of information'.

Ethics

This study was performed according to principals of good clinical practice as well as the declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee of Hannover Medical School.

Results

Patient Characteristics and Anti-viral Treatment

The 115 patients who were selected to receive a PI had a mean age of 54 years and the majority had advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. Overall, only 101 patients were treated with a PI due to a weak response or a poor tolerability to Peg-IFN/RBV therapy in the lead-in phase. A total of 69 patients were treated with TVR and 34 with BOC, including two patients who were switched from TVR to BOC during therapy due to TVR-related adverse events. The median observed PI treatment duration was 12 weeks (range: 4 days–48 weeks) (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort | Patient number | 115 |

| Age (mean ± s.d.) | 54.4 (±10.3) |

| Gender |

| Male | 66 (57%) |

| Female | 49 (43%) |

| Used PI |

| TVR | 69 (60%)* |

| BOC | 34 (30%)* |

| None | 14 (12%) |

| Duration of PI exposure |

| Median weeks | 12 |

| Min–Max | 4 days–48 weeks |

| Fibrosis stage |

| F0–F2 | 24 (21%) |

| F3/F4 | 89 (77%) |

| n/a | 2 (2%) |

| Platelets (mean ± s.d.;/nL) | 164 (±69) |

| Albumin (mean ± s.d.; g/L) | 40.8 (±4.3) |

s.d., standard deviation; PI, protease inhibitor; TVR, telaprevir; BOC, boceprevir.

*Two patients were switched from TVR to BOC (exposed to both PIs).

Drug-Drug Interactions With the Regular Out-patient Medication Assessed at Baseline

Regular out-patient medication of the 115 patients included 116 different drugs. Almost one of four patients (23%) took more than four different drugs at baseline, while only 29 patients (25%) did not have any regular out-patient medication before HCV treatment was initiated (Figure 2a). Overall, the mean number of regular drugs was 2.7 with a maximum of eleven co-medications. Most commonly used drugs were selective beta-blocking agents, proton pump inhibitors and levothyroxine (Table 2).

Table 2. The 10 most frequent drug classes in the regular out-patient medication at baseline | Drug class | ATC code (3rd level) | Number of patients (%) |

Beta-blocking agents; selective

(i.e. bisoprolol) | C07AB | 21 (18) |

Proton pump inhibitors

(i.e. pantoprazole) | A02BC | 19 (17) |

Thyroid hormones

(i.e. levothyroxine) | H03AA | 19 (17) |

Angiotensin II antagonists

(i.e. candesartan) | C09CA | 16 (14) |

Dihydropyridine derivatives

(i.e. amlodipine) | C08CA | 15 (13) |

ACE inhibitors

(i.e. ramipril) | C09AA | 15 (13) |

Thiazides

(i.e. hydrochlorothiazide) | C03AA | 11 (10) |

| Beta-blocking agents; nonselective (i.e. propranolol) | C07AA | 10 (9) |

Biguanides

(i.e. metformin) | A10BA | 9 (8) |

Propionic acid derivatives

(i.e. ibuprofen) | M01AE9 | 9 (8) |

The risk for DDIs with a PI was considered to be negligible (Category 1) for the majority of baseline drugs (62%), whereas for 29%, some DDIs were suspected, but dose modifications or careful monitoring may have been considered as sufficient for management (Category 2). Only 4% of the drugs were contraindicated for co-administration with a PI (Category 3). However, 10% of the patients took one of these contraindicated drugs. In the remaining 5% of the drugs, significant DDIs could not be excluded due to a lack of information (Category 0) (Figure 2b). This majorly affected herbal products and so-called alternative medicine. Overall, 49% of the patients were suspected to be at risk of experiencing significant DDIs, including the 7% of patients taking at least one drug belonging to risk category 0 (Figure 2c). Drug classes most often suspected to be involved in significant DDIs with a PI were thyroid hormones, dihydropyridine derivatives and herbal drugs/alternative medicine (Table 3).

Table 3. The eight most frequent drug classes in the regular out-patient medication that were suspected to may cause significant drug–drug interactions with an HCV protease inhibitor | Drug class | ATC code (3rd level) | Number of patients (%) |

Thyroid hormones

(i.e. levothyroxine) | H03AA | 19 (17) |

Dihydropyridine derivatives

(i.e. amlodipine) | C08CA | 15 (13) |

| Alternative Medicine | - | 8 (7) |

Beta-blocking agents, selective

(i.e. bisoprolol) | C07AB | 8 (7) |

Oestrogens

(i.e. ethinylestradiol) | G03CA | 3 (3) |

Alpha-adrenoreceptor antagonists

(i.e. tamsulosin) | G04CA | 3 (3) |

Glucocorticoids

(i.e. prednisolon) | H02AB | 3 (3) |

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

(i.e. escitalopram) | N06AB | 3 (3) |

Figure 2. Risk for drug–drug interactions between a protease inhibitor and the regular out-patient medication of the 115 patients prior to the initiation of anti-viral treatment: Number of different drugs in the regular out-patient medication (a). Percentage of the different drugs in the regular out-patient medication containing to risk category 1, 2, 3 and 0 for drug–drug interactions with an HCV protease inhibitor (b). Portion of patients with a high risk (taking at least one category 3 drug), an uncertain risk (no category 3, but one or more category 0 drug), significant, but no severe risk (one or more category 2, but no category 0 and 3 drugs) and those without any risk for drug–drug interactions with an HCV protease inhibitor (no or only category 1 drugs in the regular out-patient medication) (c).

Drug-Drug Interactions With Medication Started During Anti-viral Treatment

The included patients received 254 new drugs during PI treatment, mostly due to side effects of triple therapy. Most frequently, these new drugs were specific skin lotions, analgesics or antihistamines. Medications were usually prescribed by the HCV-treating physician, but also frequently by the patient's general practitioners or other physicians. In 8%, the name of the newly prescribed drug could not be evaluated retrospectively affecting 9% of the patients. In only 3% of the patients were new co-medications not suitable for co-administration with a PI. More than half of the patients (59%) either did not take any new drugs during treatment or only those considered to be safe in terms of significant DDIs with a PI (Figure S1a–c).

Impact of DDI Considerations Before and During PI Therapy

In 16% of the patients, at least one drug of the regular out-patient medication was stopped before PI treatment commenced due to suspected DDIs. In an additional 5% of cases, dose adjustments of the respective co-medication were applied before PI treatment was initiated. During PI treatment, discontinuation and dose adjustments of co-medication became necessary each in five cases (5%). Overall, suspected DDIs were managed by dose adjustments and discontinuation of co-medication before or during PI therapy in 7% and 21% of the patients respectively. In six patients (6%), a supposed treatment with certain drugs was either delayed until the end of PI therapy or an alternative medication was chosen due to DDI considerations.

Discussion

Management of drug–drug interactions (DDI) represents a challenge in the treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. We here show, in a real-world cohort of patients treated in a tertiary referral centre, that DDIs represent a considerable risk if HCV protease inhibitors (PI) are used. However, DDIs can be managed if adequate medication adjustments and precautions are followed.

DDIs have not been considered a major problem in HCV therapy before HCV protease inhibitors have been introduced in 2011. However, it is certainly not surprising that many HCV patients take several drugs not related to the liver, as documented in our study. Similar to the non-HCV-infected population, HCV patients suffer from different common comorbidities like hypertension, dysliproteinaemia or atrial arrhythmia. Furthermore, some comorbidities like diabetes and thyroid disorders may even be overrepresented in the HCV-infected population, as they have been suspected to be extrahepatic manifestations of HCV infection.[16-18] Indeed, anti-hypertensive and anti-diabetic drugs as well as thyroid hormones belonged to the most frequent drugs in the regular out-patient medication of our study cohort. However, an important finding of our study was that, although some DDIs were expected in almost half of the patients, only a relatively small portion of patients took drugs that were strictly contraindicated for co-administration with a PI. In addition, a similar number of patients took drugs for which the available drug information was insufficient to exclude DDIs. However, these drugs mainly belonged to herbal products/alternative medicines and therefore a simple discontinuation may widely be considered. Overall, only a minority of patients (n = 23) required adjustments to their pre-treatment medication before or during PI therapy. Based on these findings a careful assessment of the regular out-patient medication and subsequent evaluation of potential DDIs with a PI are absolutely crucial to ensure drug safety in all treated patients. Importantly, this assessment must also include self-medication belonging to the group of herbal products/alternative medicine.

In contrast to the pre-existing baseline medication, the majority of newly prescribed drugs during PI treatment were supposed to counter adverse events of anti-viral therapy. Here, it seems to be feasible to handle potential DDIs by establishing standard algorithms for the management of frequent adverse events like depression or rash. In such standard algorithms, drugs with well-manageable DDIs or, even better, those without any risk for DDIs with a PI should be preferred. As a result of this strategy and careful DDI consideration prior to new drug prescriptions, the risk for DDIs was lower for the newly prescribed medications during PI therapy. Still, of note and importantly, even during PI therapy, some drugs not allowed for co-administration were prescribed by other physicians and, in some cases, drug names were even unknown. This emphasises the need for a close collaboration between different physicians involved in the management of hepatitis C patients.

DDI assessment is certainly rather time-consuming if it is based on several different sources as applied in this study. Still, concentrating exclusively on the prescribing information of BOC and TVR may be insufficient as the provided data are limited. In our experience, web-based DDI interaction tools like http://www.hep-druginteractions.org represent the most feasible and comprehensive way for an assessment of potential DDIs. However, although this web resource is updated regularly and already includes a huge number of drugs, many drugs taken by our study cohort could not be found. This underlines the challenge of generating clinically useful information when comparatively few DDI studies have been performed. Therefore, more studies investigating DDIs with DAAs need to be performed in the future.

This study was not designed to compare the risk of DDIs between TVR and BOC regimens. It is well known that, in general, interactions may be more prominent for TVR. However, overall risk categories of co-medications did not differ between TVR and BOC. In a few cases of doubt or discrepancies between the two HCV PIs, the more severe risk category was chosen, which may have lead to a slight overestimation of the overall risk for DDIs. Certainly, it has to be considered that the current patient cohort may differ from those in smaller centres and may not be representative for all HCV patients due to the referral tertiary setting. As shown in a recently published analysis, patients selected for currently available triple therapy tend to be those with the more urgent need for anti-viral treatment presenting with more advanced liver disease.[11] However, this shows that, even in a complicated, difficult-to-treat cohort, the challenge of DDI appeared to be manageable. Nevertheless, risk of DDIs must not be neglected. Although only a minority was infected by a severe risk for DDIs, this still requires cautiousness and a careful evaluation of the patient's drug chart. Otherwise, there is a risk for even life-threatening complications. Severe adverse events caused by drug interactions, in particular, through the CYP3A4 pathway are reported frequently.[19-21] There also have been cases of anti-viral treatment failure in HIV patients due to DDIs.[22] Lately, there has been a case of renal failure in an HCV-infected liver transplant patient receiving TVR treatment in combination with tacrolimus.[23] In addition, a possible limitation of our study is that information on number and type of drugs widely depended on patient information. Therefore, some drugs may have been missed and risk for DDIs may have been underestimated in our study.

The next wave of DAAs including the protease inhibitors faldaprevir and simeprevir as well as the NS5B nucleotide inhibitor sofosbuvir may be available in early 2014 and more will follow in the upcoming years. Risk for DDIs differ between the various future DAA classes. The nucleotide NS5B inhibitor sofosbuvir does not seem to be involved in significant DDIs.[24, 25] In contrast, DDIs have to be considered for several nonnucleotide NS5B inhibitors.[15] DDIs may also play a role for some NS5A inhibitors. Daclatasvir is substrate and inhibitor of P-glycoprotein and substrate of CYP3A4. However, pharmacokinetic data suggest that risk for significant DDIs is far lower compared with using protease inhibitors.[15] Soon-available PIs faldaprevir and simeprevir are also both inhibitors and substrates of CYP3A4 and it has already been shown that drug levels are altered in the presence of other strong inhibitors or inducers of CYP3A4.[15] Taken together, it can be assumed that the challenge of DDIs will certainly accompany HCV therapy in upcoming years, in particular, as combination treatments with several DAAs will most likely be necessary to finally achieve an efficient interferon-free anti-viral treatment.[6, 26]

In summary, we have shown that DDIs in HCV patients are manageable, as only a minority of drugs may be unsuitable for co-administration. Still, the patients' drug charts need to be checked carefully, including self-medication, which is time-consuming and requires sufficient interaction studies provided by the pharmaceutical companies. Drug interaction websites can be regarded as an important tool to aid in the management of DDIs in clinical practice. We believe that continued support of these websites would be very useful.

References

-

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol2011; 55: 245– 64.

-

Maasoumy B, Wedemeyer H. Natural history of acute and chronic hepatitis C. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol2012; 26: 401–12.

-

Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, Belperio P, Halloran J, Mole LA. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol2011; 9: 509–16.e1.

-

van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, et al.Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA2012; 308: 2584–93.

-

Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med2013; 158: 329–37.

-

Wedemeyer H. Hepatitis C in 2012: on the fast track towards IFN-free therapy for hepatitis C? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol2013; 10: 76–8.

-

Rowe IA, Houlihan DD, Mutimer DJ. Despite poor interferon response in advanced hepatitis C virus infection, models of protease inhibitor treatment predict maximum treatment benefit. Aliment Pharmacol Ther2012; 36: 670–9.

-

Maasoumy B, Manns MP. Optimal treatment with boceprevir for chronic HCV infection. Liver Int2013; 33 (Suppl 1): 14–22.

-

Jesudian AB, Jacobson IM. Optimal treatment with telaprevir for chronic HCV infection. Liver Int2013; 33 (Suppl 1): 3–13.

-

Ramachandran P, Fraser A, Agarwal K, et al.UK consensus guidelines for the use of the protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir in genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C infected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther2012; 35: 647– 62.

-

Maasoumy B, Port K, Markova AA, et al.Eligibility and safety of triple therapy for hepatitis C: lessons learned from the first experience in a real world setting. PLoS ONE2013; 8: e55285.

-

Joshi D, Carey I, Agarwal K. Review article: the treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection in liver transplant candidates and recipients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther2013; 37: 659–71.

-

Hezode C, Fontaine H, Dorival C, et al.Triple therapy in treatment-experienced patients with hcv-cirrhosis in a multicentre cohort of the french early access programme (anrs co20-cupic) - nct01514890. J Hepatol2013; 59: 434– 41.

-

Burger D, Back D, Buggisch P, et al.Clinical management of drug-drug interactions in HCV therapy: challenges and solutions. J Hepatol2013; 58: 792– 800.

-

Kiser JJ, Burton JRJ. Everson GT. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol: Drug-drug interactions during antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C, 2013.

-

Antonelli A, Ferri C, Ferrari SM, Colaci M, Sansonno D, Fallahi P. Endocrine manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab2009; 5: 26–34.

-

Zignego AL, Ferri C, Pileri SA, Caini P, Bianchi FB. Extrahepatic manifestations of Hepatitis C Virus infection: a general overview and guidelines for a clinical approach. Dig Liver Dis2007; 39: 2–17.

-

Eslam M, Khattab MA, Harrison SA. Insulin resistance and hepatitis C: an evolving story. Gut2011; 60: 1139–51.

-

Ricaurte B, Guirguis A, Taylor HC, Zabriskie D. Simvastatin-amiodarone interaction resulting in rhabdomyolysis, azotemia, and possible hepatotoxicity. Ann Pharmacother2006; 40: 753–7.

-

Pollack TM, McCoy C, Stead W. Clinically significant adverse events from a drug interaction between quetiapine and atazanavir-ritonavir in two patients. Pharmacotherapy2009; 29: 1386–91.

-

Hoover WC, Britton LJ, Gardner J, Jackson T, Gutierrez H. Rapid onset of iatrogenic adrenal insufficiency in a patient with cystic fibrosis-related liver disease treated with inhaled corticosteroids and a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor. Ann Pharmacother2011; 45: e38.

-

Hugen PW, Burger DM, Brinkman K, et al.Carbamazepine–indinavir interaction causes antiretroviral therapy failure. Ann Pharmacother2000; 34: 465–70.

-

Werner CR, Egetemeyr DP, Lauer UM, et al.Telaprevir-based triple therapy in liver transplant patients with hepatitis C virus: a 12-week pilot study providing safety and efficacy data. Liver Transpl2012; 18: 1464–70.

-

Mathias A, Cornpropst M, Clemons D, Denning J, Symonds WT. No clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions between sofosbuvir (GS- 7977) and the immunosuppressants cyclosporine A or tacrolimus in healthy volunteers. Hepatology2012; 56 (Supplement): 1063A.

-

Kirby B, Mathias A, Rossi S, Moyer C, Shen G, Kearney BP. No clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug interaction between sofosbuvir (GS- 7977) and HIV antiretrovirals atripla, rilpivirine, darunavir/ritonavir, or raltegravir in healthy volunteers. Hepatology2012; 56(Supplement): 1067A.

-

Manns MP, von Hahn T. Novel therapies for hepatitis C – one pill fits all? Nat Rev Drug Discov2013; 12: 595–610.

Source