Hepatology

Volume 61, Issue 4

April 2015

Pages 1127–1135

David R. Nelson, James N. Cooper, Jacob P. Lalezari, Eric Lawitz, Paul J. Pockros, Norman Gitlin, Bradley F. Freilich, Ziad H. Younes, William Harlan, Reem Ghalib, Godson Oguchi, Paul J. Thuluvath, Grisell Ortiz-Lasanta, Mordechai Rabinovitz, David Bernstein, Michael Bennett, Trevor Hawkins, Natarajan Ravendhran, Aasim M. Sheikh, Peter Varunok, Kris V. Kowdley, Delphine Hennicken, Fiona McPhee, Khurram Rana, Eric A. Hughes, on behalf of the ALLY-3 Study Team

First published: 10 March 2015

DOI: 10.1002/hep.27726

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Nelson received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Merck. Dr. Lawitz consults, advises, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from AbbVie, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and Vertex. He consults, advises, and received grants from Achillion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Idenix, Novartis, Santaris, and Theravance. He consults and advises BioCryst, Biotica, and Regulus. He is on the speakers' bureau for Kadmon. He received grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Presidio, and Roche. Dr. Pockros consults, advises, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Janssen. Dr. Gitlin is on the speakers' bureau for and received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead. Dr. Freilich received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Younes is on the speakers' bureau for and received grants from Vertex, Gilead, and AbbVie. He received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Idenix, and Merck. Dr. Ghalib received grants from Gilead, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer, Salix, Pharmasset, Boehringer Ingelheim, Anadys, Janssen, Evoke, Idenix, Takeda, Vertex, Virochem, Achillion, and Debio. Dr. Thuluvath is on the speakers' bureau and received grants from Gilead and AbbVie. He is on the speakers' bureau for Onyx. He received grants from Salix and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Bernstein consults, advises, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from Gilead and AbbVie. He consults and received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Hawkins consults, advises, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from Gilead, AbbVie, and Janssen. He is on the speakers' bureau and received grants from ViiV. He received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Ravendhran advises, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from Gilead and AbbVie. He is on the speakers' bureau for Salix and Onyx. He received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck. Dr. Sheikh advises, is on the speakers' bureau for, and received grants from Gilead. He advises and is on the speakers' bureau for AbbVie. He received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Idenix, Merck, Achillion, Vertex, Genentech, and Hologic. Dr. Kowdley advises and received grants from AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. He advises Achillion and Trio Health. He received grants from Beckman, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ikaria, Intercept, Janssen, Mochida, Novartis, and Vertex. Dr. Hennicken is employed by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. McPhee is employed by and owns stock in Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Rana is employed by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Hughes is employed by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

This study was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Abstract

Treatment options for patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 3 infection are limited, with the currently approved all-oral regimens requiring 24-week treatment and the addition of ribavirin (RBV). This phase III study (ALLY-3; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02032901) evaluated the 12-week regimen of daclatasvir (DCV; pangenotypic nonstructural protein [NS]5A inhibitor) plus sofosbuvir (SOF; pangenotypic NS5B inhibitor) in patients infected with genotype 3. Patients were either treatment naïve (n = 101) or treatment experienced (n = 51) and received DCV 60 mg plus SOF 400 mg once-daily for 12 weeks. Coprimary endpoints were the proportions of treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients achieving a sustained virological response (SVR) at post-treatment week 12 (SVR12). SVR12 rates were 90% (91 of 101) and 86% (44 of 51) in treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients, respectively; no virological breakthrough was observed, and ≥99% of patients had a virological response (VR) at the end of treatment. SVR12 rates were higher in patients without cirrhosis (96%; 105 of 109) than in those with cirrhosis (63%; 20 of 32). Five of seven patients who previously failed treatment with an SOF-containing regimen and 2 of 2 who previously failed treatment with an alisporivir-containing regimen achieved SVR12. Baseline characteristics, including gender, age, HCV-RNA levels, and interleukin-28B genotype, did not impact virological outcome. DCV plus SOF was well tolerated; there were no adverse events (AEs) leading to discontinuation and only 1 serious AE on-treatment, which was unrelated to study medications. The few treatment-emergent grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities that were observed were transient. Conclusion: A 12-week regimen of DCV plus SOF achieved SVR12 in 96% of patients with genotype 3 infection without cirrhosis and was well tolerated. Additional evaluation to optimize efficacy in genotype 3–infected patients with cirrhosis is underway. (Hepatology 2015;61:1127–1135)

Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 3 is common throughout the world and remains a significant disease burden for many patients.[1, 2] Infection with HCV genotype 3 has been associated with an increased risk of progression to cirrhosis, as well as development of steatosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), compared with other HCV genotypes.[3-5] In an observational cohort study, analysis of real-world data from the Veterans Affairs HCV clinical registry found that the risks of cirrhosis, HCC, liver-related hospitalization, and death were significantly higher in genotype 3–infected patients, compared with genotype 1–infected patients,[6] underscoring the medical need for safe, effective treatment options for patients with genotype 3 infection. Recent advances have led to the approval of interferon (IFN)-free and/or ribavirin (RBV)-free therapies for chronic infection with HCV genotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4. However, for both treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients with genotype 3 infection, IFN- and RBV-free therapy options are currently limited.

Therapies approved in the United States and Europe for treatment of genotype 3 infection include a 24-week, all-oral regimen of sofosbuvir (SOF; a pangenotypic nonstructural protein [NS]5B inhibitor) in combination with RBV[7, 8] and a 24-week regimen of pegylated IFN (Peg-IFN) plus RBV.[9, 10] In addition, a 12-week, IFN-based regimen of SOF plus Peg-IFN and RBV[8] is approved in Europe for treating genotype 3 infection, as are all-oral, 24-week regimens of daclatasvir (DCV; a potent, pangenotypic NS5A inhibitor) plus SOF with RBV[11] and ledipasvir (LDV; an NS5A inhibitor) plus SOF with RBV[12] for patients with compensated cirrhosis and/or previous treatment experience. The all-oral combination of SOF plus RBV requires 24 weeks of treatment because 12- and 16-week treatment durations were associated with lower response rates (30%-61% and 62%, respectively) in genotype 3–infected patients.[7, 13, 14] With 24-week treatment, lower response rates were observed in genotype 3–infected patients who were treatment experienced (77%), particularly those with cirrhosis (60%), compared with those who were treatment naïve (93%).[7, 15] In addition, there was an increased incidence of anemia, which is consistent with the hemolytic anemia known to occur with RBV treatment.[15, 16] Thus, patients with genotype 3 infection have a need for improved treatment options, preferably with therapies of shorter duration and without the addition of Peg-IFN or RBV.

DCV was evaluated in combination with SOF in a phase II study.[17] Treatment for 24 weeks with DCV plus SOF, with or without the addition of RBV, resulted in an 89% rate of sustained virological response (SVR) at post-treatment week 12 (SVR12) among 18 treatment-naïve patients with genotype 3 infection.[11, 17] Of 5 genotype 3–infected patients who had ≥F3 fibrosis (based on FibroTest scores), all 5 achieved SVR12.11 In this phase III study, the efficacy and safety of 12-week, RBV-free treatment with DCV plus SOF were evaluated in treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients chronically infected with HCV genotype 3.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Patients

This was an open-label, two-cohort phase III study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02032901) of a 12-week regimen of DCV plus SOF in genotype 3 infection. Eligible patients were males and females ≥18 years of age with chronic genotype 3 infection who were either treatment naïve or treatment-experienced and had HCV-RNA levels ≥10,000 IU/mL at screening. Treatment-naïve patients had no previous exposure to any IFN formulation, RBV, or any HCV direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agent, whereas treatment-experienced patients received previous therapy with IFN-α (with or without RBV), SOF plus RBV, or other anti-HCV agents, such as inhibitors of cyclophilin or microRNA. Patients who received previous therapy with NS5A inhibitors and those who previously discontinued treatment with SOF plus RBV prematurely because of intolerance (other than exacerbation of anemia) were excluded. All permitted previous anti-HCV therapies must have been completed or discontinued at least 12 weeks before screening.

Patients with compensated cirrhosis were eligible (up to 50% in each cohort), with cirrhosis determined by liver biopsy (Metavir F4) at any time before screening, FibroScan (>14.6 kilopascals [kPa]) within 1 year of baseline (day 1), or a FibroTest score ≥0.75 coupled with an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI) >2. Per the study protocol, FibroTest assessments (scores determined by BioPredictive) were performed during screening; a FibroTest score ≤0.74 corresponded to a fibrosis stage of F0-F3, and a score >0.74 corresponded to a fibrosis stage of F4. Key patient exclusion criteria included chronic liver disease other than that related to HCV infection, infection with HCV genotypes other than genotype 3 or with mixed genotypes, coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis B virus, documented or suspected HCC, or evidence of hepatic decompensation.

All patients received open-label treatment with DCV 60 mg plus SOF 400 mg once-daily for 12 weeks, with a subsequent 24-week follow-up. The study was conducted in accord with the ethical principles that originated in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site. All patients provided written informed consent before participation in the study.

Study Assessments

Adherence to study treatment was assessed at each study visit based on tablet counts and dosing information recorded in patient diaries. HCV-RNA levels were determined at baseline; on-treatment weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12; and post-treatment weeks 4, 12, and 24 using the COBAS TaqMan HCV test (version 2.0; Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA), with a lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) of 25 IU/mL. HCV genotype or subtype was determined using the RealTime HCV genotype II assay (Abbott Molecular, Abbott Park, IL) and confirmed by viral sequence analysis. Interleukin-28B (IL28B) genotype (rs12979860 single-nucleotide polymorphism) was determined by polymerase chain reaction amplification and sequencing. Resistance testing was performed by population-based sequencing of plasma samples from all patients at baseline and from patients with virological failure (VF) who had HCV-RNA levels of ≥1,000 IU/mL. VFs included virological breakthrough (VBT), defined as a confirmed, on-treatment HCV-RNA increase of ≥1 log10 IU/mL from nadir or a confirmed HCV-RNA measurement of ≥LLOQ following a previous measurement of <LLOQ; relapse, defined as a confirmed HCV-RNA measurement of ≥LLOQ post-treatment following an undetectable HCV-RNA measurement at the end of treatment; and HCV-RNA measurement of ≥LLOQ at any time point not meeting the definition of VBT or relapse. Safety and tolerability were assessed based on adverse event (AE) reporting, clinical laboratory tests, vital signs, and physical examinations.

Statistical Analyses

The coprimary endpoints were the proportions of treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients achieving SVR12 (defined as HCV-RNA levels <LLOQ, either detectable or undetectable). Target sample sizes of 100 treatment-naïve and 50 treatment-experienced patients would provide 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the observed SVR12 rates of within 9.7% and 14.2%, respectively, when the observed SVR12 rates were ≥75%. In the treatment-naïve cohort, a target sample size of 100 patients would provide a 95% CI lower bound of >76% with an observed SVR12 rate of 85%. In the treatment-experienced cohort, a target sample size of 50 patients would provide a 95% CI lower bound of >73% with an observed SVR12 rate of 86%.

Secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportion of patients achieving HCV-RNA levels <LLOQ, detectable or undetectable, at on-treatment weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8, the end of treatment, and post-treatment weeks 4 and 24; the proportion achieving HCV-RNA levels <LLOQ, undetectable, at on-treatment weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 and the end of treatment; and SVR12 rates by baseline cirrhosis status and IL28B genotype. Efficacy analyses included all patients who received ≥1 dose of study medications, and response rates and two-sided 95% exact binomial CI were estimated by cohort for efficacy endpoints.

Results

Patients

A total of 152 patients received ≥1 dose of study medications; of these, 101 (66%) were treatment naïve and 51 (34%) were treatment experienced. Treatment-experienced patients included those who had previously failed treatment with IFN-based therapies or other anti-HCV therapies, including SOF- and alisporivir (ALV)-containing regimens (Table 1). One hundred (99%) treatment-naïve patients and all 51 (100%) treatment-experienced patients completed 12 weeks of treatment; 1 treatment-naïve patient discontinued treatment after week 8 because of pregnancy, but achieved SVR12.

Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Disease Characteristics

Overall, patients were 90% white and 59% male, with a median age of 55 years; the majority of patients had baseline HCV-RNA levels of ≥800,000 IU/mL (71%) and a non-CC IL28B genotype (61%; Table 1). All patients were chronically infected with HCV genotype 3. Cirrhosis, as determined by liver biopsy, FibroScan, or FibroTest/APRI per protocol, was present in 21% of patients overall (treatment naïve, 19%; treatment experienced, 25%). Fibrosis stage was also determined using FibroTest scores, based on which, 119 (78%) patients had a fibrosis stage of F0-F3 and 30 (20%) had a fibrosis stage of F4; FibroTest scores were not reported for 3 patients (all 3 achieved SVR12). Baseline albumin levels were similar in patients with cirrhosis (median, 41 g/L; range, 33-47) and without cirrhosis (median, 44 g/L; range, 36-53); baseline platelet (PLT) counts were lower in patients with cirrhosis (median, 124.5 × 109/L; range, 62-382) than in those without cirrhosis (median, 200 × 109/L; range, 89-334).

Virological Response

DCV plus SOF for 12 weeks achieved SVR12 rates of 90% in treatment-naïve patients and 86% in treatment-experienced patients with genotype 3 infection, with an overall SVR12 rate of 89% (Table 2). Rapid and sustained reductions from baseline in HCV-RNA levels were observed, with mean decreases of 4.3-4.5 log10 IU/mL at on-treatment week 1 and 4.7-4.9 log10 IU/mL at on-treatment week 2. The proportion of patients achieving HCV-RNA levels <LLOQ, detectable or undetectable, at early on-treatment time points in the treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced cohorts, respectively, was 40% and 24% for week 1, 77% and 69% for week 2, and 94% and 98% for week 4. HCV-RNA levels were undetectable at end of treatment in ≥99% of patients.

Table 2. Virological Response

The relationship between virological response (VR) at early on-treatment time points and achievement of SVR12 was assessed. SVR12 was achieved by 94% of patients with HCV-RNA levels <LLOQ, detectable or undetectable, and 86% of patients with HCV-RNA levels ≥LLOQ, at week 1; 92% and 79% of patients with HCV-RNA levels <LLOQ, detectable or undetectable, or ≥LLOQ, respectively, at week 2 achieved SVR12. Among patients with HCV-RNA levels <LLOQ, detectable or undetectable, at week 4, 90% achieved SVR12, compared with 71% of patients with HCV-RNA levels ≥LLOQ. When VR at week 4 was assessed based on undetectable HCV-RNA levels, the proportion of patients with a week 4 response who achieved SVR12 was 91%.

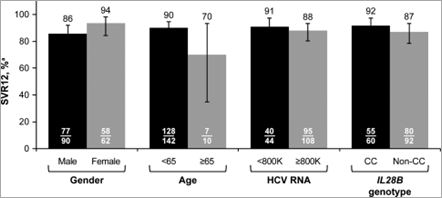

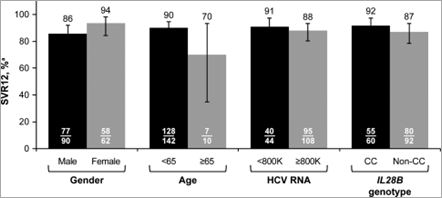

Analysis of SVR12 in patient subgroups based on baseline characteristics showed no notable differences by gender, age, HCV-RNA levels, or IL28B genotype (Fig. 1). Among treatment-experienced patients, SVR12 was achieved by 25 of 31 patients with previous relapse and by all 7 null responders, 2 partial responders, and 2 patients who experienced VBT with past treatment. In addition, all 6 patients who were intolerant of past treatment achieved SVR12, as did 2 of 3 patients with other types of past treatment failure (HCV-RNA never undetectable on treatment or indeterminate). SVR12 was achieved in 5 of 7 patients who previously failed treatment with an SOF-containing regimen and in both patients who previously failed treatment with an ALV-containing regimen.

Figure 1. VR by baseline characteristics. aHCV RNA <LLOQ (25 IU/mL), detectable or undetectable; error bars reflect 95% CI.

SVR12 rates were higher in patients without cirrhosis (96%) than in patients with cirrhosis (63%; Fig. 2A), although high response rates at end of treatment were noted both in patients with and without cirrhosis (97% and 100%, respectively). A similar trend was observed when SVR12 was analyzed by fibrosis stage, based on FibroTest scores, of F0-F3 (93%) and F4 (70%; Fig. 2B). Overall, results by cirrhosis status or by fibrosis stage based on FibroTest scores were generally consistent between the treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced cohorts. VR at early on-treatment time points did not appear to impact SVR12 rates in patients with cirrhosis, given that the proportion of patients with cirrhosis who achieved SVR12 was the same among those who did or did not have undetectable HCV-RNA levels at on-treatment week 4 (10 of 16 patients with undetectable HCV-RNA levels at week 4 and 10 of 16 patients without undetectable HCV-RNA levels at week 4 achieved SVR12).

Figure 2. VR in patients with (A) cirrhosis or (B) fibrosis stage of F4 (FibroTest). aHCV RNA <LLOQ (25 IU/mL), detectable or undetectable; error bars reflect 95% CI. bAmong 32 patients with cirrhosis, 11 (34%) had baseline PLT counts ≤100 × 109 cells/mL. cCirrhosis status determined in 141 patients by liver biopsy (Metavir F4), FibroScan (>14.6 kPa), or FibroTest score ≥0.75 and APRI >2; for 11 patients, cirrhosis status was missing or inconclusive (FibroTest score >0.48 to <0.75 or APRI >1 to ≤2). dPer the study protocol, FibroTest assessments were performed during screening (FibroTest scores not available for 3 treatment-naïve patients); F0-F3 defined as FibroTest score of ≤0.74 and F4 defined as FibroTest score of >0.74.

The relationship between resistance-associated variants (RAVs) at NS5A amino acid positions M28, A30, L31, and Y93 at baseline and SVR12 was assessed. No patients had L31 polymorphisms at baseline; 1 patient without cirrhosis had M28V at baseline and achieved SVR12. NS5A-A30 polymorphisms were detected in 14 of 147 patients at baseline. Of the 14 patients with A30 polymorphisms, 9 of 9 without cirrhosis and 1 of 5 with cirrhosis achieved SVR12. Among the 4 patients with cirrhosis with baseline A30 polymorphisms who did not achieve SVR12, 2 also had Y93H at baseline, 1 had A30T, which has no effect on DCV potency in vitro, and 1 had A30K, which was associated with SVR12 in the 5 remaining patients with this polymorphism.[18] NS5A-Y93H was detected in 13 of 147 patients who had NS5A sequence at baseline; of these 13 patients, 6 of 9 without cirrhosis and 1 of 4 with cirrhosis achieved SVR12. No NS5B RAVs were detected at amino acid positions associated with resistance to SOF (159, 282, or 321) at baseline.

Virologic Failure

Occurrence of VF was low, with no VBTs observed (Table 2). One treatment-naïve patient with cirrhosis had a quantifiable HCV-RNA level of 53 IU/mL at end of treatment; this event did not meet the protocol definition of VBT, which required on-treatment confirmation of the HCV-RNA measurement. The patient was a slow responder through week 4 and had a low baseline PLT count (83 × 109 cells/L), reflecting advanced cirrhosis. Sixteen patients (9 treatment naïve and 7 treatment experienced) had post-treatment relapse, of whom 11 (7 treatment naïve and 4 treatment experienced) had cirrhosis at baseline. All of the relapses occurred by post-treatment week 4 except for 1, which occurred between post-treatment week 4 and post-treatment week 12 in a treatment-naïve patient without cirrhosis. Factors that may have contributed to treatment failure in this patient included a very high baseline HCV-RNA level (27.5 × 106 IU/mL), presence of the NS5A-Y93H RAV at baseline, and incomplete treatment adherence (93% adherent), although no relapses occurred among the other 4 patients who were not completely adherent to treatment (3 with 90%-95% adherence and 1, who discontinued after week 8 because of pregnancy, with 66% adherence). The NS5A-Y93H RAV emerged in 9 of 16 patients with relapse; of the remaining 7 patients with relapse, 6 had NS5A-Y93H at baseline and 1 had emergent NS5A-L31I. NS5B RAVs at amino acid positions associated with resistance to SOF (159, 282, or 321) were not detected at relapse.

Safety and Tolerability

DCV plus SOF was well tolerated, with no AEs leading to discontinuation of treatment (Table 3). There were no deaths and only 1 serious AE (SAE) was reported on-treatment: an event of gastrointestinal hemorrhage that was considered not related to study medications. The most common AEs (in >10% of patients) were headache, fatigue, and nausea, and the incidence of grade 3 AEs was low (2%), with no grade 4 AEs reported.

Table 3. Safety and Tolerability

Few treatment-emergent grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities were observed with DCV plus SOF, with such events reported only for absolute lymphocytes, PLTs, international normalized ratio (INR), and lipase. Incidences of these grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities were low (≤2% each), and none led to clinically significant bleeding or pancreatitis or to treatment discontinuation. Moreover, these abnormalities were primarily transient increases or decreases that were not present for prolonged periods during treatment. No treatment-emergent grade 3/4 abnormalities were observed in hemoglobin (Hgb) or liver-related parameters, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and AST and total bilirubin.

Discussion

In patients chronically infected with HCV genotype 3, the all-oral, 12-week regimen of DCV plus SOF achieved SVR12 rates of 90% in treatment-naïve patients and 86% in treatment-experienced patients; SVR12 was achieved in 96% of patients without cirrhosis and in 63% of patients with cirrhosis. No VBTs were observed, and all but 1 patient achieved a VR at end of treatment. The combination of DCV plus SOF was well tolerated, with a low incidence of SAEs, no deaths or AEs leading to discontinuation, and few treatment-emergent grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities. These results are generally consistent with those from a phase II study demonstrating the efficacy and tolerability of DCV plus SOF, with or without RBV, in patients with genotype 3 infection.[17] Overall, findings from the present study show that in genotype 3–infected patients without cirrhosis, a 12-week treatment with DCV plus SOF is efficacious, compared with the current 24-week, all-oral regimens containing RBV.

SVR12 rates were comparable across subgroups based on gender, age, baseline HCV-RNA levels, and IL28B genotype. Notably, this study included patients who previously failed treatment with SOF- or ALV-containing regimens, of whom 71% and 100%, respectively, achieved SVR12. A limitation of the study is that the impact of race on SVR12 rates could not be fully assessed owing to the high proportion of white patents enrolled (90% overall); however, all 6 of the black patients enrolled in the study achieved SVR12.

SVR12 rates with DCV plus SOF were higher in patients without cirrhosis than in those with cirrhosis, and in patients with a fibrosis stage (based on FibroTest scores) of F0-F3 than in those with F4. However, the 63% SVR12 rate in patients with cirrhosis is comparable to that achieved with 16 (61%) or 24 weeks (67%) of SOF plus RBV, with the advantages of an IFN-free and shorter-duration regimen.[7] On-treatment and end-of-treatment response rates were similar in patients with or without cirrhosis, with relapse accounting for all but one of the treatment failures: among the 16 patients with relapse, 11 had cirrhosis. Relapse was more frequent in the 4 patients with cirrhosis who had Y93H RAVs at baseline, although these RAVs did not measurably affect on-treatment response. Other possible reasons for the higher relapse rate in genotype 3–infected patients with cirrhosis remain uncertain. Given that high relapse rates have also been observed with other all-oral regimens after treatment of genotype 3 infection,[14, 18] this HCV genotype may be more difficult than others to eradicate with DAAs, particularly in patients with cirrhosis. Multiple factors may contribute to this effect and require further study.

The robust on-treatment VR with DCV plus SOF, with nearly all VFs the result of post-treatment relapse, suggests that optimizing treatment outcomes in patients with cirrhosis could include the addition of RBV or a longer treatment duration. A randomized study has been initiated (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02319031)[19] in which patients with genotype 3 infection and compensated advanced cirrhosis are receiving DCV in combination with SOF and RBV for 12 or 16 weeks, with the objective of determining whether adding RBV and extending treatment will improve the durability of response post-treatment. This strategy has been successful with other all-oral regimens. A recent report regarding a phase II study of SOF plus GS-5816, with or without RBV, suggests that the addition of RBV improves response rates in genotype 3–infected patients with cirrhosis. In treatment-experienced patients with cirrhosis treated for 12 weeks, SVR12 rates were higher with SOF plus GS-5816 with the addition of RBV (85%-96%) than with sofosbuvir plus GS-5816 alone (58%-88%).[20] The combination of LDV plus SOF with RBV for 12 weeks has been reported to provide SVR12 rates of 89% in genotype 3–infected, treatment-experienced patients without cirrhosis and a lower rate of 77% in those with cirrhosis.[21] Because DCV has shown greater potency in vitro against genotype 3, compared with LDV,[11, 22-24] the combination of DCV plus SOF, with the addition of RBV, may be expected to provide improved response rates relative to the current results in patients with cirrhosis. DCV plus SOF, with or without RBV, is also being evaluated in additional patient populations with high unmet medical needs in other studies of the ALLY phase 3 program. These include patients who have cirrhosis or who are post–liver transplant (ALLY-1; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02032875) and patients who are coinfected with HIV (ALLY-2; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02032888). DCV has been approved in combination with other anti-HCV agents in Europe and Japan.

DCV plus SOF was associated with a favorable safety profile. Incidences of SAEs and grade 3/4 AEs were low, and no deaths or AEs leading to discontinuation were reported. Few grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities were reported, and the events that were observed were primarily transient changes and did not lead to treatment discontinuation. No grade 3/4 abnormalities in Hgb emerged during treatment, whereas previous studies have reported reductions in Hgb levels with the combination of SOF plus RBV.[14, 15] Overall, no notable safety concerns were observed with the combination of DCV plus SOF.

In summary, a 12-week regimen of DCV plus SOF achieved SVR12 in 96% of treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients with genotype 3 infection without cirrhosis and was well tolerated. This regimen, without the addition of RBV and with a shorter treatment duration relative to currently approved all-oral regimens, demonstrated high SVR12 rates across patient subgroups, except in patients with cirrhosis and regardless of past treatment response. These findings support the 12-week regimen of DCV plus SOF as an efficacious, well-tolerated treatment option. Additional evaluation to optimize efficacy in genotype 3–infected patients with cirrhosis is underway.[19]

References

Source